Editor's note: Since ancient times, Xinjiang has been a multi-ethnic region with many religions living side by side. In 60 B.C., Xinjiang officially became part of China’s territory when the Western Han Dynasty established the Protectorate of the Western Regions. Many archaeologial discoveries in Xinjiang, as among them the Nia site where the ancient city of Jingjue in the novel Candle in the Tomb is located, have unearthed Han and Western Jin Dynasty Chinese inscriptions; The Cangjie Chapter, a Chinese textbook for practicing characters passed down during the Han Dynasty, Buddhist literature and the boom of the Silk Road. Throughout Xinjiang’s long history, the various ethnic groups living in the region have mingled and learned from one another, creating a pluralistic pattern.

Candle in the Tomb begins with the ancient city of Jingjue. Why did the author of this novel think of using the ancient city of Jingjue as the setting? Perhaps inspired by The Book of Han - Xiyuzhuan? Or maybe Jingjue is a cool name, like a cold code with a profound meaning.

What is Jingjue?

The story starts in the Han Dynasty, when China’s possession of the Western Region (including Xinjiang) began during the reign of Emperor Wu (140-87 B.C.). At that time the area west of Yangguan and Yumen Pass was called the Western Regions. In addition to military conquests in strategic regions like Loulan, Emperor Wu sent Zhang Qian (164-114 BC) and other envoys to Central Asian oasis states such as Da Yuezhi, Da Xia, Wusun and Dawan. In 60 B.C., the second year of Emperor Xuan’s reign, the Han Dynasty officially established the Protectorate of the Western Regions to manage the north and south of the Tianshan Mountains.

The knowledge of the west, especially the Protectorate of the Western Regions, gained by the Han envoys far exceeded that of the pre-Qin period, the source of information when the Han historian Ban Gu compiled The Book of Han-Xiyuzhuan. These western city-states, which the Han Dynasty enfeoffed, were populated by tribes of various sizes carried over from the early Iron Age, some of which spoke ancient Indo-European languages. Jingjue was one such small state on the southern tract of the Tarim Basin, whose name first appeared in The Book of Han-Xiyuzhuan.

In the record of Xiyuzhuan, the King of Jingjue governed the city, with a population of 480 families and 3,360 people. Around the time of the annexation in the early Han Dynasty, Jingjue was incorporated into Shanshan, a large state in the southeastern Tarim Basin; this situation continued until Shanshan’s extinction in the fourth century A.D. The large number of Qulu documents found from the Nia site also ended.

Why is this small state translated as Jingjue in Xiyuzhuan? These two words look very much like Chinese. However, according to the rules of Chinese translation of Hu, a non-Chinese language, and Chinese phonetics at that time, it is now known that Jingjue is the comparative sound of the ancient city of Cad’ota in the Qulu documents excavated from the Nia site. In Qulu script, this place name refers to the local area of the Nia site, connecting the location of Jingjue and the Nia site.

Looking for Jingjue Kingdom in Niya Ruins

Niya Ruins is in the hinterland of the Taklamakan Desert, north of Minfeng County, Xinjiang, and near the oasis of Niya River.

The ancient city was discovered in 1900 by a British explorer, Aurel Stein, with the help of local guides. Preserved beneath the sand were astonishing city ruins. Stein continued his adventures in 1906 and 1930, and excavated many relics.

While other explorers visited the Niya ruins after Stein, it was not until the 1990s that scientific-based archaeological survey and excavation were implemented.

Back then, the Sino-Japanese Joint Archeological Team, joined by the Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, RyuKoku University in Japan and other organizations, carried out nine-year archeological research and excavation from 1988 to 1997.

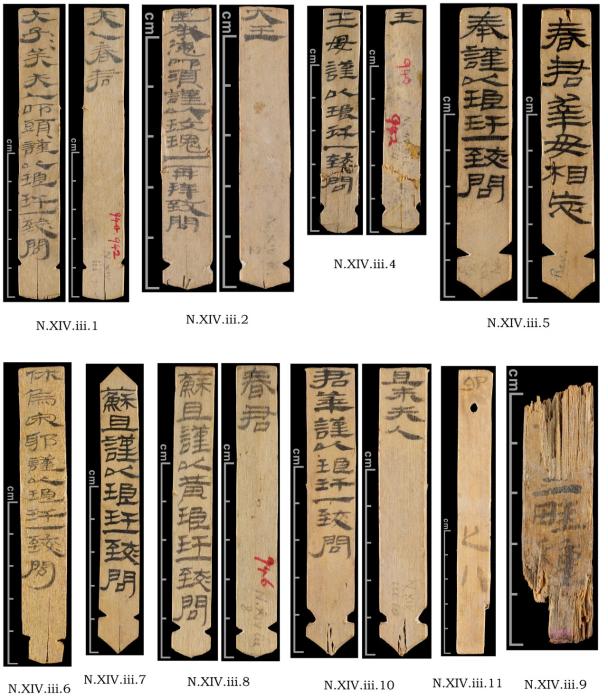

Stein first proposed the idea that Niya was Jingjue Kingdom in the Han and Jin dynasties, and Wang Guowei, a famous Chinese scholar (1877-1927), agreed. Sir Stein further found a Han strip with Han Jingjue King Chengshu Congshi at Niya during his 1931 expedition to Central Asia. This evidence convinced Wang and others holding the same opinion.

An amazing view may be seen at Niya: a chain of dune connecting building remains scattered along the ancient delta. Within the site, 215 relics were found -- city ruins, houses, workshops, a Buddhist pagoda, livestock circles, fruit gardens, coffins and even bridges -- along with thousands of ancient items. All of these can revive the once-prosperous city in deep desert along the Silk Road.

It is rare in world history to find such rich relics and items, as well as unearthed relics of amanuensis including historical documents written in Chinese, Kharosthi language of Niya and the Sogdian language of the Jingjue Kingdom.

The most eye-catching items are a great number of official documents written in Chinese and Kharosthi; the famous silk fabric woven with 五星出东方利中国, meaning “Five Stars rise in the East, benefiting China,” and other silk fabric unearthed from coffins. Among the architectural remains, Buddhist buildings stand out, among them the Sudubo pagoda and the Buddhist ruins in N5 courtyard, where wooden towers and delicate frescoes were discovered.

The main part of the Kharosthi documents has already been interpreted and translated. This language, which originated in the Buddhist center Gandhara along the Indus Valley, is used in Buddhist scriptures. Kharosthi, together with the Brahmi and Sogdian languages, was used in the Silk Road trade during the Han and Jin dynasties. For example, the well-known Sogdian Books found in Dunhuang Beacon remains of the Han Dynasty recorded Sogdian businessmen’s business reports and letters home while they did silk trade in China.

Political and Cultural Soft Powers of the Han Dynasty

Chinese bamboo strips unearthed at Niya, dating to the Han and Western Jin dynasties, included Han strip with Han Jingjue King, the memorial to the emperor written by the Qiemo royal lineage, and the imperial decree by Western Chin Emperor Szu-ma Yen to the Western Regions. The Han strip with Han Jingjue King is an imperial decree to the Western Regions, offering a glance at the Han Dynasty administration in remote regions. These documents can be related to those discovered in the Dunhuang Beacon remains of the Han Dynasty.

Another set of Han bamboo strips attracted Wang Guowei’s attention came from a large house in the northern part of the Niya site in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The words on the strips refer to giving langgan and rose (both are ancient jade jewelries) as gifts. The gift-givers are the queen mother, the crown prince, and people named Chengde, Junhua, Su Qi and Xiuwu Songye. The receivers are the king; the vassal kings and their wives; Chunjun (apparently a title), and Madame Qiemo. The words on the strips are written with warmth: “Together with the message, I would like to send a jade pendant to Chunjun. Please do not forget me.” It might be a love letter.

As the Chinese characters on the strips are in the official script style of the Han Dynasty, and expressions like “bow again” and “kowtow” are courteous, scholars wondered who the writer was. In 1993, this question was answered when wooden strips with the texts of Cangjie Pian, a teaching book for calligraphy in the Han Dynasty, were discovered at Niya. Cangjie Pian, Ji Jiuzhang, a book to teach children to read and write in the Han Dynasty, and calendars have also been discovered at the beacon tower site in Dunhuang, Gansu Province, proving that the Han Dynasty promoted its culture in the northwest border counties and the Western Regions of ancient China. Han Dynasty culture also penetrated upper-class culture of the Hu nationality in the Western Regions.

In addition to the bamboo strips, some high-quality items from the central China in the Han Dynasty have been unearthed from the ruins, including silk, Wu Zhu coinage, lacquer ware, and bronze mirrors. These show a deep integration of different cultures in the Western Regions. A large amount of silk is sewn into different styles of clothing, with front lapels either on the right or left.

These silks are of fine quality, woven with intricate and beautiful patterns. Some are woven with inscriptions like “Five stars rising in the East benefit China” and “Long live the descendants of princes.” Some silks were the rewards given by emperors of the Han and Jin dynasties, and those who could wear them should be the royal family or the upper classes of the ancient Kingdom of Jingjue, the Niya site today.

A recent study of tombs at Niya has also uncovered some rituals and customs that originated in the central China in the Han Dynasty. For example, the huiyi (rod racks for clothes) placed in the tombs to hang the funeral objects of the deceased are different for men and women. Some burial bows and arrows for men seem related to Chinese ritual archery stemming from ancient times. One more example is that a rooster was placed beside the head of one tomb occupant. In central and eastern China, these ritual activities are usually found only in documentary records, without archaeological evidence.

The Ancient Kingdom of Jingjue on the Silk Road

The archaeological discoveries at Niya confirm that Jingjue was a station on the Silk Road, which benefited its economic and cultural prosperity.

Silk was the most striking discovery. In addition to high-quality silk, there were also ordinary silk and pieces of cloth from central and eastern China. An interesting discovery is the silks wrapped around one bow and one bowstring, on which Chinese characters and Kharosthi characters were written in ink, respectively. The one in Chinese is inscribed “One piece of silk given by Yang Ping from Xiuruo Town, Henei County,” telling the number of silks and the origin by giving the name and location of the person who handed over the silk.

How did this silk come to Jingjue? Coincidentally, Stein also found two silks inscribed in Chinese and Brahmi in the beacon tower site in Dunhuang in 1901. The Chinese one reads, “A piece of silk from Kangfu town, Ren Cheng County,” with a width of around two chi and two cun (2.2 chi, 73 centimeters), a length of around four zhang (13 meters), a weight of 25 liang (1.25 kilograms), and a value of six hundred and eighteen qian (copper coins), and the Brahmi texts was interpreted as “certain cloth with length of 46 Zha,” a measurement by hand spans; one Zha equals around 20 centimeters. Wang Guowei speculated that the Chinese one was military supplies transferred to the border during the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-24 A.D. The Brahmi one is considered a commodity destined for somewhere in India.

Indeed, the Chinese and Kharosthi documents of Niya and Loulan include many documents about silk trading. The Ancient Book of Suet shows that there was an active silk trade during the Han-Jin period (202 B.C.-420 A.D.) from Dunhuang and other border counties to Loulan, Cad’ota, and Samarkand. It was dominated by the Da Yuezhi and Suthep merchants, with Han and Jin governments in Dunhuang and the west also involved. It was precisely at the Niya site that a set of “passports” was found, issued by the Western Jin government to a Kushan merchant named Zhi Zhu, which were probably the most ancient “passport” in the world.

The silk trade is only one aspect of the Silk Road. The extensive and deep cultural exchanges it promoted brought great benefits. Its glorious aspect was multiculturalism, which also resulted in harmonious development. In this small oasis society, in addition to mainstream Buddhism, other religious beliefs, such as witchcraft and some forms not yet known, are reflected in the archaeological remains and the Kharosthi documents.

Several Buddhist texts are preserved in the Kharosthi of Niya, including the Dhammapada, the precepts and a text on the prayer for the festival of the bathing Buddha. There is even a Statute of the Sangha that provides for the silk punishment for monks who violate it. It is important to note that these documents are among the earliest dated Buddhist texts ever discovered.

The discovery of bamboo strips from the Han Dynasty, such as the Cangjie Chapter, shows how Chinese and Chinese characters were used in the upper layer of Cad’ota. In addition, the Loulan-Cad’ota dialect spelled in Kharosthi is a mixture language of Chinese, Greek, Iranian, Tugholo, Überese, and SutheNiyan, fully illustrating the cultural phenomenon of Cad’ota: communication and integration.

Also noteworthy is the Greek cultural influence on the Cad’ota: some Kharosthi script square seals use images of Greek deities like Athena and Heracles. Two of the seals were stamped with both Han and Western-style seals. The richness and diversity of the excavated artifacts vividly show how the Jingjue, which was on the Silk Road, forged its own culture.

The disappearance of Cad’ota is full of drama. After the Three Kingdoms, it was no longer recorded. In 644 A.D., Xuanzang passed through a place called “Niyang” on his way back from India to obtain Scriptures; it was already a swamp at that time.

It is always intriguing to speculate on the reasons for the demise of this oasis civilization. Claims of river diversions, migrations, plagues, wars, etc., all lack sufficient evidence to date. To return to the beginning of the topic, the ancient city of Cad’ota is real and its buried history more colorful than people can imagine.

Author: Liu Wensuo (professor of anthropology, head of the Teaching and Research Section of Archaeology at Sun Yat-sen University)

This article was first published by CNA on March 21, 2021.

京公网安备 11010202009201号

京公网安备 11010202009201号