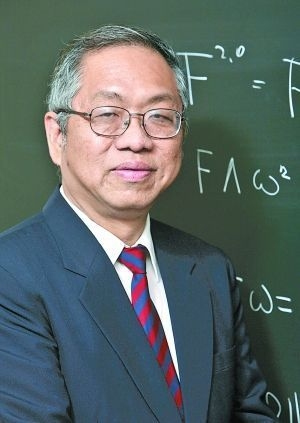

(Ecns.cn)--"When I was young, I did not like going to school, and even dropped out for about half a year to play happily with my friends," said Shing-Tung Yau, a well-known mathematician, Wednesday at the first lecture of the Shanghai Book Fair.

"At that time, the only pressure came from my father who pushed me to practice reading and writing and to recite poems. I had to read excerpts from literary works of modern China and foreign countries," Yau continued.

Yau added that he was actually not interested in them at all and could only finish the first several chapters of the Dream of the Red Chamber, one of the Four Great Classical Novels of China, until the death of his father, which changed his attitude toward literature completely.

"The early death of my father and the decline of my family reminded me of The Dream of the Red Chamber," noted Yau, who began since to appreciate its minute and smooth descriptions of the rise and decay of two wealthy noble families.

For over four decades of being a mathematician, Yau often refers to it when solving mathematical problems. "Cultivating affection is very important to studies," explained Yau, adding that it was the fluctuating emotion that had aroused his interests in exploring the mysteries of math.

To Yau, literature also provides him with power to overcome difficulties. "Nobody can be successful all the time. However, some chose to work harder after failure; while some give up their dreams," said Yau.

Yau always compares math to literature, believing that math, quite similar to novels, can never be ivory-towered. "Some scholars now are blindly in pursuit of publishing their research results in the Science Citation Index in a bid to get noticed and then funded. However, those publications are in fact meaningless, and that is very sad."

"Good math should refer to various natural phenomena. Only by doing which can the studies be meaningful and classical," Yao added.

Yau also likes Shiji, or Records of the Grand Historian, a work of Chinese history from the time of the Yellow Emperor around 2600 BC until the author's own time during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC―9 AD), from which he learnt to be decisive.

"Historical stories teach us how to make decisions at critical periods. Appropriate decisions made by historical figures can serve as examples," said Yau.

Undoubtedly, one of the best decisions he has made was to major in math at university, which enabled him to exert his talents and make significant contributions later.

"Yau really is a genius," Robert Greene told The New York Times, a mathematician at the University of California, Los Angeles. "The quantity and quality of the math he has done is overpowering。"

In 1976, Yau successfully solved the Poincaré conjecture, a famous 100-year-old problem about the structure of space.

Moreover, he is in fact best known for inventing the mathematical structures known as Calabi-Yau spaces that underlie string theory, the supposed "theory of everything." In 1982 he also won a Fields Medal, the mathematics equivalent of a Nobel Prize.

Everybody now agrees that Yau is one of the great mathematicians of this age.

Richard Hamilton, a friend of Dr. Yau and a mathematician at Columbia University, told The New York Times that Yau had built "an assembly of talent attracted by his energy, his brilliant ideas, and his unflagging support for first-rate mathematics, people whom Yau has brought together to work on the hardest problems."

Born in Guangdong Province in 1949 and brought up in Hong Kong, Yau's life was not all roses. As one of eight children of a college professor of philosophy, he grew up rather poor without electricity or running water in a village.

He was even the leader of a street gang and often skipped school, reported The New York Times.

Yau's father died when he was only 14, leaving the family destitute and in debt. But he had instilled in Yau a love of literature and philosophy.

"In fact, I felt I could understand my father's conversations better after I learned geometry," he said at a talk in 2003, reported The New York Times.

With the abstract thinking learned from his father, the young Yau retreated into his studies, working as a tutor to help pay the debts.

At the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Yau soon emerged as a talented mathematician, leaving for graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley in 1969 when he was just a junior.

By the end of his first year he had collaborated with a teacher to prove conjectures about the geometry of unusually warped spaces.

He was the student of Chen Xingshen, then widely recognized as the greatest living Chinese-born mathematician. He attained a doctoral degree merely two years later at UC Berkeley.

Though having settled in America for decades, Yau, a Chinese, never forgot to help his home county develop mathematics by educating Chinese students, establishing mathematics research institutes and centers, organizing conferences at all levels, and raising private funds for these purposes.