By Liu Guanguan

The Asian Art Museum has a collection of nearly 20,000 Asian cultural relics spanning 6,000 years, with Chinese artifacts dominating. Jay Xu, the museum's director and CEO, talks about the museum's role as a bridge in cross-cultural communication. The key to setting culture free from political limits is to find "the greatest common denominator." Museums can transcend politics and highlight the communication between peoples and cultures.

CNS: You have work experience in both Eastern and Western museums. What was the biggest difference you found when you joined a Western museum?

Jay Xu: I began to work for American museums in 1996 as a curator in the Chinese art department at the Seattle Art Museum. At that time, what impressed me most was the difference in the Chinese and American management styles. Chinese museums work in teams, while American museums emphasize individuals. In comprehensive museums in the United States, it is often impossible to have dedicated personnel for every cultural category, one person has to do many jobs. This mechanism has great advantages. When you work on your own, you have many opportunities to utilize your talents. But the challenge is that no one can do everything, so American museum personnel have to cooperate with Chinese experts outside the museum.

CNS: As a Chinese-American, what are your advantages when working in American museums? And what are the challenges?

Jay Xu: My identity gives me considerable advantage when participating in a cooperation project with China. It's because I have worked in China and share the views of my Chinese colleagues. In addition, I worked as secretary to the museum director at the Shanghai Museum for seven years, which was a great opportunity to learn how to operate a museum. It helped me a lot when working in the United States.

At the same time, my identity also creates challenges. There is a Chinese saying, "See more than you've seen and learn more than you’ve learned." We Chinese-Americans need to know more about Chinese culture and broaden our horizons so that we can think of Chinese culture and art from a global perspective. We need to know both Chinese culture as well as the diverse cultures worldwide profoundly.

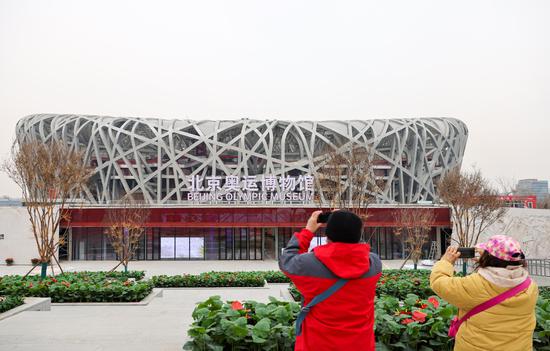

CNS: Western museums generally display Chinese historical artifacts in all China-themed exhibitions. Visitors are always shown "the ancient and old China." When will they present the modern and contemporary China to visitors?

Jay Xu: The Asian Art Museum will always protect and promote traditional art as well as embrace the future. We pay attention to both traditional art and modern art. We exhibit modern art and also display ancient art from a contemporary view. The emphasis on tradition is not at all contradictory to modernization.

CNS: How can museums maintain a balance between elitism and popular culture?

Jay Xu: We live in an era of diversity, not duality. Elitism is not contradictory to popular culture. We conduct our work based on first-class academic studies, and we are pretty willing to work with scholars in the ivory tower. On the other hand, our visitors are from all walks of life, so we need to present the most profound academic studies to them in an easy-to-understand and interesting way.

For example, our museum's most popular exhibit is a ritual vessel in the shape of a rhinoceros. It is a bronze object estimated to be from the period 1100–1050 BC. It is also our mascot. We conducted an online poll asking for a name for the object and someone even suggested a Spanish name, Reina, meaning "queen." As an expert on bronzes, I am familiar with this ritual object but I have not yet figured out its sex because the ancient artisan did not add any sex features to it. The voting showed that someone in the public regarded it to be female, even a noble queen.

CNS: How can we tell the story of Asia, especially China, to the West?

Jay Xu: The key to telling the story of Asian and Chinese culture in the West is "communication" and "connection." You need to find a point of introduction that is familiar to the Western audience to lead them into unfamiliar cultures.

The first point is to connect the ancient with the modern.

We once held an exhibition where half of the exhibits were ancient artifacts from our collection and the other half were works by contemporary artists. Putting them together enabled the audience to see how contemporary artists were inspired by ancient art. Such exhibitions shed light on ancient art from the perspective of contemporary art and harness the vitality of ancient art.

The second point is to connect Asia with the rest of the world.

A few years ago, we organized an exhibition, "China in the Middle of the World," with world maps as the theme. The maps on display included the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu or the Map of the Ten Thousand Countries of the Earth, a woodblock print on fine paper printed in the late Ming Dynasty, and the Kunyu Quantu,the Complete Map of the World developed by a Jesuit priest, Ferdinand Verbiest, during his mission to China in 1674, the early Qing Dynasty. Both maps were customized for the Chinese emperors by Western missionaries who worked together with Chinese printers and engravers and both placed China in the center of the world. Maps are an important means for people to understand the world, and with them as a medium, this exhibition reflected China's position in the world as well as the exchanges between it and other countries at that time.

The third point is to connect art with life.

This connection is particularly important. All of our exhibitions need to have something to do with American life today. In 2013, the Asian Art Museum organized an exhibition on the Terracotta Warriors and their horses (sculptures denoting the army of the first Chinese emperor, Qin Shi Huang, which were buried with the emperor in 210 BC in what is today the city of Xi'an in central China). The exhibition was themed "Immortality." We hoped the visitors would better understand the theme when they saw the exhibition. Everyone is capable of immortality. If a teacher produces good students, if a community volunteer helps the elderly, or a scientist makes an important discovery, they have all achieved immortality. And this pursuit is universal. The theme was to make the audience understand why Qin Shi Huang had so many terracotta warriors and horses made and left so many wonderful relics.

CNS: What can Chinese and Western museum professionals learn from each other?

Jay Xu: In the United States, all museums enjoy autonomy and different museums have their distinct features. This is something that Chinese museums can learn from, especially considering the rapid development of China's museums in the past 20 years. The architecture of the museums around China is not the same, but most museums are similar regarding the forms and even the contents, with the exception of a few leading ones. Each region has much room for highlighting its uniqueness in its museums.

One major dilemma for Western museums is operation, which has been particularly acute since the pandemic. Their major source of funding is not the admission fee but donations from individuals, associations and corporations, which puts considerable fundraising pressure on the curators. In contrast, the Chinese Government provides Chinese museums with a lot of support in terms of operating funds. I hope the U.S. Government can learn from this and give more support to cultural endeavors.

CNS: What is the role of museums in cross-cultural exchanges?

Jay Xu: People have different interests and hobbies, even those from the same cultural background, and there are greater differences between different cultures. If the political systems of two countries are different as well, then the divergences will be even greater. How to achieve cultural exchanges that go beyond the limitations of politics? We need to find the greatest common interest between countries. Museums transcend the political level and emphasize people-to-people and cross-cultural communication.

When countries celebrate friendly relations, cultural and sports activities are held, showing the role of cultural exchanges as the icing on the cake. When there are serious contradictions between countries, cultural activities are organized to defuse the crisis, which, as the Chinese proverb goes, is like "offering fuel in snowy weather" or breaking the ice. For example, China and the United States successfully established diplomatic relations following "ping-pong diplomacy," playing table tennis together, and cultural exchanges. Hence, regardless of the state of political relations between countries, cultural communication must not be stopped, especially for countries with poor political relations.

京公网安备 11010202009201号

京公网安备 11010202009201号