(Ecns.cn) – In a 2009 Forbes Magazine survey, the Chinese mainland ranked second in a list of countries or regions with the harshest tax regimes in the world, following France. That list was recently reposted online by Web users and ignited an intensive debate over the degree of China's tax burden.

In September, the Ministry of Finance released the latest statistics on China's fiscal revenue in the first eight months of 2011, which show that about 80% of revenue came from taxes, up 30.9% compared with the same period in 2010.

Netizens and scholars hold different viewpoints on the issue, but after seeing Forbes' list from 2009, many are convinced that China's tax burden is high compared to other countries.

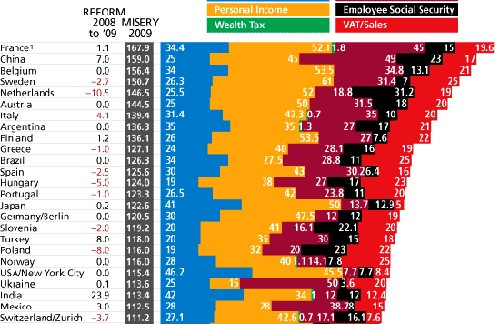

Zhou Jiangong, chief editor of the Chinese edition of Forbes, responded to questions about the survey. Zhou said the ranking was based on Forbes' Tax Misery and Reform Index, which calculates taxation according to the highest marginal percentage in each locale. The purpose of the ranking is to establish a measurement by which the tax burdens of different countries or regions can be compared. Using this measurement, the survey was conducted fairly, said Zhou.

Tax burden and tax misery: two different things

In response to China's "miserable" score, Zhou focused on three important issues: the calculation method of the index, the statistical standards of tax burden and the relationship between tax burden and tax misery.

The Forbes Tax Misery and Reform Index picks the highest rate from each tax category – including corporate income tax, personal income tax, property tax, employer social insurance, employee social insurance and value added tax (or sales tax) – and then adds the rates of these categories together. It uses a personal income tax rate of 45%, which is the maximum marginal tax rate of individual tax in China.

Though there have been many questions about this method of calculation (the real tax rate is usually lower than the nominal one, for example, and the highest rate only applies to a very small group of taxpayers), Zhou said it was purely for maintaining uniformity, since tax systems are very complicated and differ from country to country.

Zhou also emphasized that tax burden is different from tax misery. When calculating the tax burden of a country, there are two different statistical standards used internationally. One comes from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the other from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Using either of these two standards, China's macro tax burden is much lower than that of the U.S., Japan, Germany and many other developed countries. However, tax misery indicates the genuine feeling of taxpayers about their tax burden. If the government provides high-quality and satisfying public services, taxpayers will suffer less from tax misery.

It also was pointed out that the more misery taxpayers suffer from, the higher the tax burden they must bear, and if public services are insufficient to satisfy taxpayers, those services need to be improved.