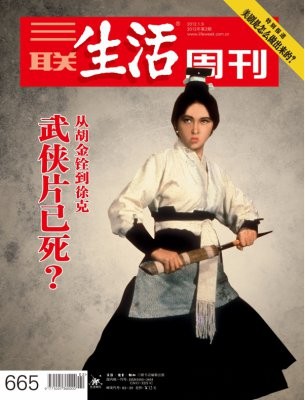

Wuxia films, China's heroic martial arts genre, may have mired in a dilemma currently, with two of its leading directors, Hu Jinquan and Tsui Hark, appearing to adopt extreme positions in taste.

Wuxia films, China's heroic martial arts genre, may have mired in a dilemma currently, with two of its leading directors, Hu Jinquan and Tsui Hark, appearing to adopt extreme positions in taste: the former tries his best to create realistic scenes for fiction, while the latter embeds as many special effects as possible into his productions.

Hu, a Hong Kong and Taiwan-based director, inaugurated a new generation of wuxia films in the late 1960s with such well-known works as Come Drink with Me (1966), Dragon Gate Inn (1967) and A Touch of Zen.

Hu's masterpiece, A Touch of Zen is the chief exemplar of his blend of Zen Buddhism and unique Chinese aesthetics; it won the Technical Prize at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival.

Yet, the film did not come into being easily. Constantly striving for realism, Hu had spent nine months building an outdoor set of over a hundred antique houses, which, back in the 1960s, was enough to try patience of both cast and crew. An expert in the history of ancient China, Hu always conducted meticulous research on the costumes as well and invested handsomely in ideal wardrobes, which pushed up production costs and frightened away producers.

Despite his blazing successes, Hu could hardly make ends meet in his late years. He made a brief return from semi-retirement in the 1990s, when Tsui Hark invited him to film The Swordsman, a film with a troubled birth that became a famous wuxia movie.

Undeterred, Hu continued to devote himself to perfecting every historical detail, thus unduly prolonging the preparation time; it brought Tsui's company to the verge of bankruptcy. He finally left the project midway, leaving less than one month for Tsui and his team to complete the film.

Tsui takes a different approach from Hu, preferring to apply various fantastic technical effects to reproducing fictional scenes true to life.

His debut film, The Butterfly Murders (1979), was an eccentric and technically challenging blend of wuxia murder mystery, science fiction and other fantasy elements.

Tsui's work in 2010, Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame, was also a rare but successful blend of wuxia, suspense-thriller, mystery, and comedy, which was nominated for the Golden Lion award and won numerous others.

In his latest film--Flying Swords of Dragon Gate—Tsui employed nine special effects companies. Yet, type-cast as a member of the "New Wave" of young, iconoclastic directors, commentators from Life Week magazine and others have charged Tsui of making technically fantastic films that are empty of content. "The choices and troubles that beset Hu and Tsui are also challenges to the wuxia film industry as a whole. Movies that are too faithful to history won't find favor with investors, and works without a good story and engaging theme will not stand the test of time," the magazine pointed out.

Kung Fu Panda, however, is an innovation on China's wuxia films, especially those from the 1970s. "The most amazing part is that Hollywood made a comprehensive study of the martial arts in Chinese films prior to making this animation, thus the kung fu played by Paul the panda is familiar to many people," analyzed the Life Week. "But Chinese wuxia movies haven't made any big breakthroughs yet in terms of quality."

Some say domestic wuxia films have been emphasizing the importance of seeking vengeance, bringing villains to justice, giving vent to anger and discontent, and few heroes portrayed in the movies can be described as "xiake"—martial artists who follow the code of "xia" that can be likened to the Anglo-Saxon myth of Robin Hood.

The word wuxia is a compound word composed of the words "wu," which means "martial," "military," or "armed" and "xia," meaning "honorable," "chivalrous," or "heroic." Typically, the heroes in Chinese wuxia fiction do not serve a lord, wield military power or belong to the aristocratic class. They are often from the lower social classes of ancient Chinese society, and "xiakes" usually have considerable martial arts abilities that are used not just for personal gain, but employed to achieve the greater good, explains "A Definition of Wuxia and Xia" on heroic-cinema.com.

Copyright ©1999-2011 Chinanews.com. All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.