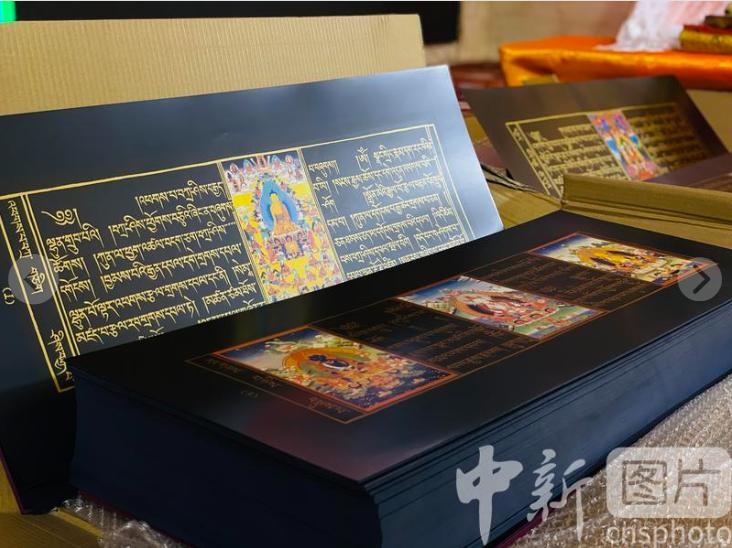

The photo shows sections of the Golden-Script Tripitaka (Kangyur).

When discussing Tibetan Buddhism, two terms are frequently encountered: "Indo-Tibetan Buddhism" in Western academia, and "Sino-Tibetan Buddhism" among Chinese scholars. What, then, is the historical relationship between Han Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism? And why does the term "Sino-Tibetan Buddhism" more accurately capture the essence of their intertwined histories?

Pillars of Chinese cultural heritage

Each major tradition of Indian Buddhism, encompassing Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions, has been maintained in China. These correspond to the three primary linguistic expressions of Buddhism: Chinese, Tibetan, and Pali Buddhism, commonly referred to as Han Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Southern Buddhism, respectively.

Buddhism first entered China during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), and developed through the eras of the Three Kingdoms (220–280), Jin Dynasties (265–420), and Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), culminating in an era of cultural prosperity symbolized by "the 480 temples of the Southern Dynasties." By the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, eight major sects had emerged, namely Tiantai, Sanlun (East Asian Mādhyamaka), Faxiang (Dharmalaksana, also called Weishi), Hua-yen, Chan (Zen), Pure Land, Vinaya, and Esoteric schools. Poems with lines such as "The sound of the bells at Cold Mountain Temple, outside Suzhou city, reaches the ferries at midnight" and "How many respectable monks there are, their verses are widely copied and distributed" epitomize the extent of Han Buddhism's influence. It merged with Confucianism and Taosim, and intergrated within the cultural and intellectual fabric of the Chinese literati.

Buddhism was introduced to Tubo (today's Xizang) in the mid-7th century through pathways from both central China and India. A pivotal moment in the development of Tibetan Buddhism was the arrival of Princess Wencheng of Tang Dynasty in Xizang, who brought sacred scriptures and statues. She founded the Ramoche Temple and initiated the translation of Buddhist sutras with the assistance of monks from inland China. Over the following centuries, Tibetan Buddhism flourished and branched into the Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, Jonang, and Gelug schools. The verse "Ten thousand candles fill the purple sky, four thousand halls shine with splendor" eloquently captures the grandeur of Gelug monasticism, as exemplified by Kumbum Monastery.

As Buddhism took root in the Central Plains, it began to synthesize with Confucian and Taoist philosophies, giving rise to Chan Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, and, in more contemporary times, Humanistic Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism, meanwhile, evolved through its interactions with the native Bon tradition, resulting in a unique balance between esoteric rituals with exoteric teachings.

Throughout their respective evolutions, Han Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism absorbed myriad aspects of Chinese culture. Confucian ethics, Taoist philosophies, and rituals from Taoism and Bon —became integral elements. The architectural splendor of Buddhist temples reflects this cultural symbiosis: Han-style pagodas with their elegant, upturned eaves and intricate bracket systems coexist alongside the red walls and gilded rooftops characteristic of Tibetan monastic complexes. Buddhist scriptures have been compiled into grand canons written in Chinese, Tibetan, Manchu, and Mongolian, serving as testaments to this cultural confluence. Artistic treasures such as Thangka paintings and meticulously crafted sculptures stand as enduring symbols of this fusion. This integration not only enriched the corpus of Buddhist doctrine but wove Buddhism into the very fabric of Chinese civilization, solidifying it as an inseparable aspect of the nation's cultural identity.

Historical exchanges

Though Han Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism trace distinct lineages, they share profound affinities. Both traditions venerate an identical pantheon of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, uphold the Mahayana ethos of boundless compassion and altruism, and emphasize a symbiotic practice of wisdom and meditation as the path to enlightenment and Buddhahood. Their philosophical underpinnings reveal shared reverence for the doctrines of Mādhyamaka, Yogachara, and Tathāgatagarbha (Buddhist terms), while the Buddhist canon serves as the cornerstone of their respective scholarly pursuits. Monastics in both traditions adhere to the same vinaya, maintaining rigorous observance of monastic precepts in daily life.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907), the Tubo Kingdom dispatched emissaries to the Central Plains on multiple occasions, seeking sacred texts and learned monastics. The Tang court responded by sending eminent monks such as Liangxiu and Wensu, who each undertook two-year rotations in Xizang. Among the monks who spent time in Xizang, Chan Master Tankuang was especially favored by King Trisong Detsen, who engaged him in profound dialogue. The resulting compilation of their exchanges, known as The Twenty-Two Questions of the Mahayana, remains a testament to the era's spiritual discourse.

There was also a monk from the Central Plains, known as Mahayana, who went to Xizang and introduced a groundbreaking meditation practice. His teachings emphasized the transcending of both negative and positive thoughts, striving for a state of absolute mental stillness to achieve enlightenment. This novel approach met with widespread support, inspiring a significant following and igniting fervent debates on the merits of sudden enlightenment versus gradual cultivation. Such philosophical discussions enriched the theoretical framework of both Han Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism, fostering deeper intercultural and interreligious exchanges between the two.

The Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) also marked to a unique chapter in this historical exchange. The last emperor, Zhao Xian, after being defeated by Kublai Khan of the Yuan Dynasty (1206–1368), was sent to Xizang for religious study. Settling at the Grand Buddha Temple in Zhangye, Gansu, he immersed himself in the Tibetan language and dedicated himself to translating Tibetan Buddhist texts into Chinese. In recognition of his contributions to the spread of Buddhism, Zhao Xian was honored with the title Master of Harmony and Reverence.

Kublai Khan harbored a deep reverence for Buddhism, frequently engaging with monastic teaching and dedicating time away from state affairs to reciting sutras and to meditative practice. Noticing discrepancies in different versions of Buddhist scriptures—ranging from linguistic differences to variations in phonetic rendering—Kublai convened respected Han and Tibetan monks to scrutinize and reconcile these translations. Their research revealed that despite the disparities in wording, the essence of the teachings remained harmoniously aligned.

Throughout the Yuan Dynasty, influential Tibetan monks also contributed significantly to the propagation of Buddhism by composing texts, disseminating teachings, conferring precepts, constructing temples and stupas, crafting statues, translating sacred scriptures, and performing elaborate rituals. Among them, Phagpa, the fifth leader of the Sakya School and the first Imperial Preceptor of the Yuan court, authored numerous works at his residence at the sacred Wutai Mountain. The Collection of Histories of Han and Tibet recounts, Phagpa ordained and tonsured over 4,000 monks and nuns from all over the country, as well as Nepal and India. He also dispatched his disciples nationwide to ordain 947 individuals in one year, who in turn guided countless monks and practitioners, revitalizing Buddhism in the south Yangtze River region.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the central government bestowed honorary titles upon distinguished Tibetan Buddhism monks. The Qing Dynasty (1616–1911) saw a continuation of this exchange, with the Third Janggiya Khutukhtu and the Sixth Panchen Lama leading significant Buddhist ceremonies in China's heartland.

During the Republic of China (1912–1949), prominent figures such as Master Dayong and lay practitioner Hu Zihu organized study delegations to Kham-Xizang Region, fostering further scholarly engagement. In 1919, the Janggiya Khutukhtu visited Shanghai, delivering teachings at the Liuyun Chan Temple. By April 1925, the Ninth Panchen Lama's visit to Shanghai drew over a thousand attendees eager to hear his sermons. The Seventh Janggiya Rölpé Dorjé, revered as the "Master of Pure Enlightenment and Auxiliary to the Teachings," undertook a pilgrimage to Mount Emei in 1932, leading chanting and prayer assemblies in homage to Samantabhadra. In 1937, Master Sherab Gyatso was invited to lecture in the central regions, receiving a warm reception from a cross-section of society.

Why did Han and Tibetan Buddhism coexist and flourish for centuries?

The interconnection between Han and Tibetan Buddhism manifests in multifaceted ways. One notable example lies in the reciprocal translation of scriptures. During the Tang Dynasty, the distinguished monk Chos-grub translated several significant Han Buddhist texts into Tibetan, including The Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra: Chapter on Armored Ornaments, The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, The Laṅkāvatāra Wisdom Sutra, and The Nirvana Sutra. Similarly, the renowned monk Shariputra translated works authored by Phagpa from Tibetan into Chinese. The Ming Dynasty witnessed further collaboration, with the Tibetan Kangyur being printed in Nanjing during the Yongle era and the Tengyur during the Wanli period. The Qing Dynasty achieved a remarkable synthesis by producing the Tripiṭaka in four languages: Chinese, Tibetan, Manchu, and Mongolian.

Additionally, there was significant cross-pollination of doctrinal interpretation. Sakya Pandita, observed: "In later times, as Buddhism waned in Xizang, the teachings of the Han master Mahayana were followed only in their literal sense. Their original designation was lost, and they came to be known as Mahāmudrā. What is now called Mahāmudrā is fundamentally the meditation practice of Han Buddhism."

The reciprocal exchange between Han and Tibetan Buddhism is also vividly illustrated in the realms of architecture, sculpture, and painting. Architecturally, the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa stands as a testament to this synthesis, seamlessly blending Han, Tibetan, and Indian styles. During the Yuan Dynasty, the construction of over ten Tibetan Buddhist temples in Beijing, such as Shengshou Wan'an Temple, Datianshou Wanning Temple, and Dahuoguo Renwang Temple, further exemplified this cross-cultural integration. In the realm of sculpture, Rinchen Skyabs, in charge of Buddhism affairs of Jiangnan Region, oversaw the creation of the "Esoteric Stone Inscriptions of Feilai Peak," which featured guardian deity statues imbued with the distinctive stylistic elements of the Tibetan Buddhist Sakya School. Another notable artifact is the "Imperial Edict Stele of the Great Yuan Preceptor" at the Great Lingyan Temple in Changqing, Shandong, which bears a bilingual inscription—Chinese script on the lower half and Tibetan script on the upper—demonstrating the harmonious confluence of these traditions. Additionally, structures such as the White Pagoda of Miaoying Temple in Beijing and the Stupa of Chan Master Puzhao at Baiyun Temple in Huixian, Henan, reflect the Tibetan stupa style that flourished during the Yuan era.

These examples underscore that, from the Tang Dynasty onward, Han and Tibetan Buddhism engaged in sustained interaction, forming the foundational structure of Chinese Buddhism. As a result, Buddhism became a crucial bridge for communication and cultural exchange between the Han and Tibetan communities.

In light of this, the term "Sino-Tibetan Buddhism," as proposed by Chinese scholars, more accurately reflects historical reality compared to the "Indo-Tibetan Buddhism" label used by Western academics. China has meticulously preserved the essential corpus of Indian Buddhism, which, over time, largely disappeared from its birthplace. Although modern India has seen a revival of Buddhism, it pales in comparison to its former stature. Exaggerating the connection between Indian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism does not conform to historical fact. Consequently, the concept of "Sino-Tibetan Buddhism" aligns more authentically with the historical record.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of DeepChina.

The author is Sun Wuhu, professor and Ph.D. advisor at the School of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Minzu University of China, and Li Yue, a young scholar and PhD student at Minzu University of China.

Editor/ Liu Xian

Translator/ Deng Zhiyu

京公网安备 11010202009201号

京公网安备 11010202009201号