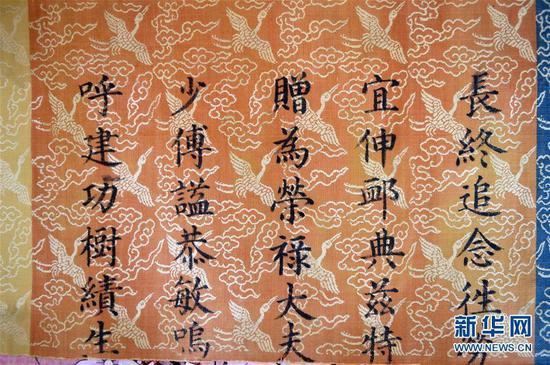

A villager surnamed Zhao in Longjiapu in Lianggang county, North China's Hebei Province, stands on a field where the local government has plants medicinal herbs for a new investment project. The project makes use of transferred land to fight poverty. (Photo: Chen Qingqing/GT)

Sharing the burden

To fight poverty in the countryside, some villages in North China's Hebei Province have implemented a land transfer program that aims to make the use of arable land more market-driven. It's collective farming in a new incarnation. Longjiapu village and Xiaolan village are among those trying out the concept. They are located in northwestern Hebei, one of the most remote areas west of the Taihang Mountains. The majority of the villages' residents live on incomes below the regional poverty line. The Global Times recently visited the villages to look into how well local authorities have done in their fight against poverty. This is the second part of a two-part story.

On a sunny Wednesday afternoon, Zhao Hongshou, a 62-year-old farmer in -Longjiapu village, in northwestern of North China's Hebei Province, hung out with some of his neighbors at a small playground near his house, which had recently been partially renovated with the help of the local government.

"My old house would have collapsed if they [local officials] hadn't helped me repair it," said Zhao, noting that he had been receiving about 100 yuan ($14.76) a month because he qualifies for the minimum livelihood guarantee, or dibao, which is distributed by the local government.

However, Zhao has not received any help from authorities since July, as "local officials have had to rebuild files and scrutinize residents' personal information to make sure that those who receive money from the government are really living below the poverty line," Zhao told the Global Times on October 26, noting he was told that the local dibao scheme is expected to resume after the files are complete.

Zhao, a local farmer who had spent decades raising sheep, recently sold every one of his 60 sheep for 20,000 yuan so he could pay back his debts for the repairs. "The local government provided about 15,000 yuan to repair my house, and I borrowed the rest from my relatives," he said.

Although his roof no longer leaks on rainy days, Zhao has nothing in the new house except a bed and some blankets to keep him warm.

"I don't have money to buy other stuff, and I have nothing to do," he said.

In addition to raising sheep, Zhao used to plant corn that earned him about 2,000 yuan a year, but since the beginning of 2016, the village has taken over all the arable land.

In 2015, Longjiapu village had a population of 868 people, of which 686 were living below the regional poverty line, according to the Hebei Poverty Alleviation Foundation, citing the latest data. The average annual income for an individual was 2,600 yuan.

The local government of Baoding, where Longjiapu village administratively belongs to, said it has pulled 700,000 people out of poverty over the past five years, according to the government's website. For example, the local government has implemented new industries in several villages in the area, pushing the average individual income above 6,000 yuan per year.

Plots for shares

The local government has paid the village 180,000 yuan this year in poverty alleviation funds, and it has introduced new industries, according to information posted on a bulletin board in the village.

Most of China's farmland is owned collectively by the people who work on it. After the rural workforce began to migrate to cities in search of better paying jobs, the central government in 2008 allowed farmers to rent out, transfer or merge the land amid a reform to bolster modern farming and make better use of unworked land, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

As part of the central government's goal of eliminating poverty by 2020, the land use policy has been geared more toward developing local industries in recent years, according to a government white paper entitled China's Progress in Poverty Reduction and Human Rights, which was published on October 17.

The villagers can transfer their land to make an investment in which every one has a share. Usually, the alleviation funds from central and local governments go into this investment, and villagers benefit from it by receiving a fixed return every year.

The farmers play a major role in investment and enjoy a guaranteed return. The investment in Longjiapu village covers 20 hectares of arable land, all transferred from local residents, to plant medicinal herbs and walnut trees.

The project is considered more profitable than farming corn. "Our farmland is now all managed by the local government," said a 67-year-old villager surnamed Zhao.

Mixed returns

With a guaranteed return on the investment in their farmland, villagers in Longjiapu should have received 800 yuan per year, and they could earn more by participating in businesses such as managing weeds and applying fertilizers, but the reality is more disappointing, some villagers told the Global Times on October 26.

Part of the farmland that the local authority invested in was halfway up a hill in the village, which was overgrown with grass and weeds. The land wasn't cultivated before the seeds were sown. "I don't think it will be productive like this," Zhao said.

Because no one in the village has received a return on investment as of yet, some villagers decided to apply for jobs removing weeds on the farm. Liu Shifang, a 39-year-old villager, is one of them.

"But the job is temporary, I get paid about 20 yuan a day, and they don't always hire people," she said.

The village is not the only one that introduced a cooperative-farming program to fight poverty.

Xiaolan village, a few miles away from Longjiapu, has also introduced new industries such as planting sweet potatoes and building a sweet potato processing factory since 2015. And the total investment is more than 300,000 yuan, said Song Zesheng, the village representative working closely with the local government.

"The annual guaranteed return plus payments to occasional workers will be thousands of yuan every year, which is definitely higher than the income for farming corn," he told the Global Times on October 26.

However, when he stepped into a local resident's home, a 60-year-old villager surnamed Zhao asked anxiously when they could get back 800 yuan as the guaranteed return. "I don't have the land anymore," she said. "The only thing I care about is how I can live if there is no temporary work."

"They will get the money soon," Song promised. He noted that the local authority has also been trying to improve villagers' quality of life by building an entertainment center in the village.

"Our efforts are all about building a modern village, and we'll definitely eliminate poverty," he said.