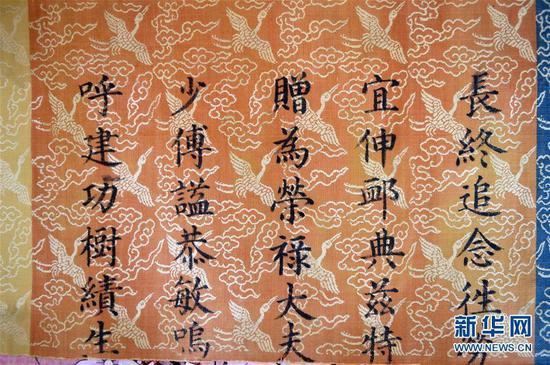

More than 2 million yuan earned via money laundering was handed over to police by a suspect at an underground bank in Guangzhou, Guangdong, in April last year. Xinhua

The nation's financial authorities are tackling money laundering by improving the mechanisms used to track suspect flows of funds.

Yan Feng (not his real name) used to operate a small store that sold liquor and snacks on a street near the ferry port in Shenzhen, Guangdong province.

Although the store appeared no different to any other outlet in the business-dominated city, which stands adjacent to Hong Kong and was the site of China's first Special Economic Zone, close acquaintances knew the family used the premises as a front for a well-developed underground bank.

For a year, Yan and his family helped clients to move amounts far in excess of the annual $50,000 foreign currency limit to regions outside the mainland, including Hong Kong and Macao, which have no currency restrictions.

Acting on Yan's instructions, clients transferred money to bank accounts under his control. Once the deposit had been made, Yan's accomplices in Hong Kong placed an equivalent amount in a local bank using Hong Kong dollars. The client was then able to transfer the money to an account of their choice anywhere in the world, but to all intents and purposes no irregular transaction had taken place.

Yan was just one of many "black bankers" in China's coastal regions who offer quick fund-transfer services and move hundreds of millions of dollars out of the country every day. Although no official figures are available, unconfirmed estimates claim about $10 billion is laundered through China every year, mostly via outbound transactions.

Growing concerns

As key components in the money laundering sphere, the activities of underground banks have become a growing concern for China's financial institutions in recent years, and their success has raised questions about the lack of regulations to combat the practice.

"Foreign complaints about Chinese money laundering are not new, but some complainants have exaggerated the situation," said Jin Luo, director-general of the anti-money laundering bureau at the People's Bank of China, the nation's central bank.

Rather than being a haven for money laundering as some people believe, China does not have the fundamentals to become a hub for illegal activities, according to Jin.

China joined the Financial Action Task Force - an intergovernmental agency founded in 1989 to fight money laundering and other illegal financial activities - in 2007.

"Since then, China has been striving to meet the rising expectations of the international community," she said, adding that one significant move was the improvement of systems to track suspect capital flows through financial institutions.

Although Yan Feng and his partners dispersed their transactions across a number of banks to avoid suspicion, the Shenzhen branch of Bank of China, a commercial lender, used a new system designed to tackle money laundering and traced 183 accounts opened by the family for use in illegal foreign-exchange transactions.